Lead Firm Strategy Implementation – Indonesian Blue Swimming Crab

Overview

In 2015, Wilderness Markets completed a value chain summary of the blue swimming crab (BSC) fishery in Indonesia in which we analyzed the current state of fishery data systems, resource management, infrastructure, and enterprise capacity. Based on these findings, we recommend a lead firm strategy to move the fishery toward sustainability. Like many fisheries in emerging markets, the Indonesian BSC fishery lacks reliable data and, despite new national policies, functions largely without effective management. The value chain has strong, established commercial and social relationships, indicative of the power and influence of a small group of 16 processors buying from 400 mini-plants that, in turn, purchase crab from more than 65,000 fishermen.

In this case, the lead firm is a U.S. based company, Blue Star Foods. Blue Star is working to create financial and social incentives to enable fishermen to transition faster to sustainable fishing practices. Through its purchasing power and relationships, Blue Star is therefore in strong position to influence the practices of a range of processors, who have commercial relationships with a network of mini-plants, collectors, and fishermen.

Sumatran vessel with collapsible traps

Lead Firm Pilot Design

With Blue Star and local harvesters, we are developing an investment model based on a pilot partnership between the lead firm and a fishing cooperative (in development). The model brings together philanthropic and private capital and provides financial, social, and environmental returns. It includes:

- Purchase commitments based on price, quality and standards

- Investments in fishermen cooperatives to motivate gear improvements

- Improved fishery data collection and traceability

- Support for harvest control compliance

This pilot is designed to attract private, return-seeking impact investment and complement ongoing work by NGOs to improve fishery management. We expect this approach will enable local fishermen to adopt sustainable practices faster than waiting for the government to independently create and enforce management changes, and without the economic hardship for fishermen that often accompanies changes in fishery regulations. It will also bolster business advocacy for more effective fisheries management policies and enforcement through a local cooperative structure.

BSC fisherman with new vessel tracking device

Goals and expected outcomes

Ultimately, as a result of better data collection and effective management, the fishery will produce higher yields of BSC. It will also provide a traceable, sustainably harvested product with a competitive advantage in key U.S. and E.U. markets. This will then allow Blue Star and supporting investors to recoup their investments in sustainable practices.

By embedding this lead firm work within existing value chain relationships and practices, we aim to:

- Demonstrate the financial viability of investments in fishery data collection and management, thus attracting additional private investment in these practices.

- Create new norms that are sustained because of their business value and not ongoing philanthropic support or government subsidies.

- Provide clear and reliable financial benefits for small-scale fishermen to make gear changes; follow harvest control measures; and take on other sustainable fishing practices. Immediate economic well-being is thereby aligned with sustainable practices to improve compliance and reduce the localized short-term, negative impacts of fishery restrictions.

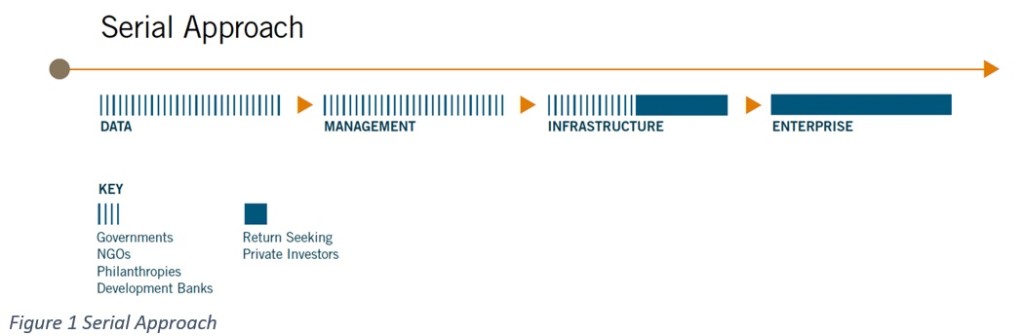

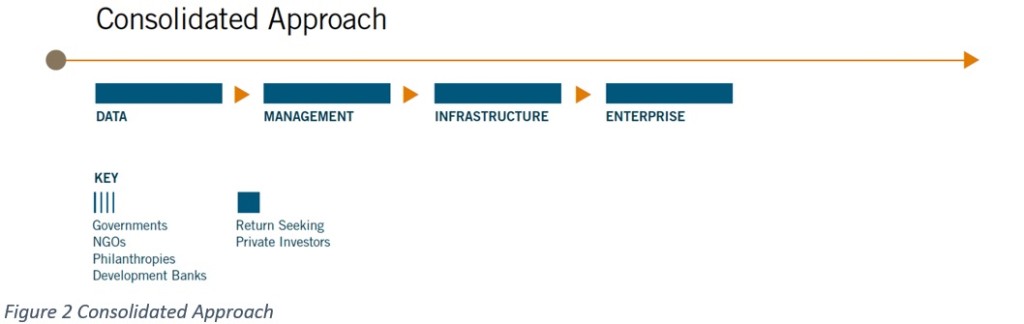

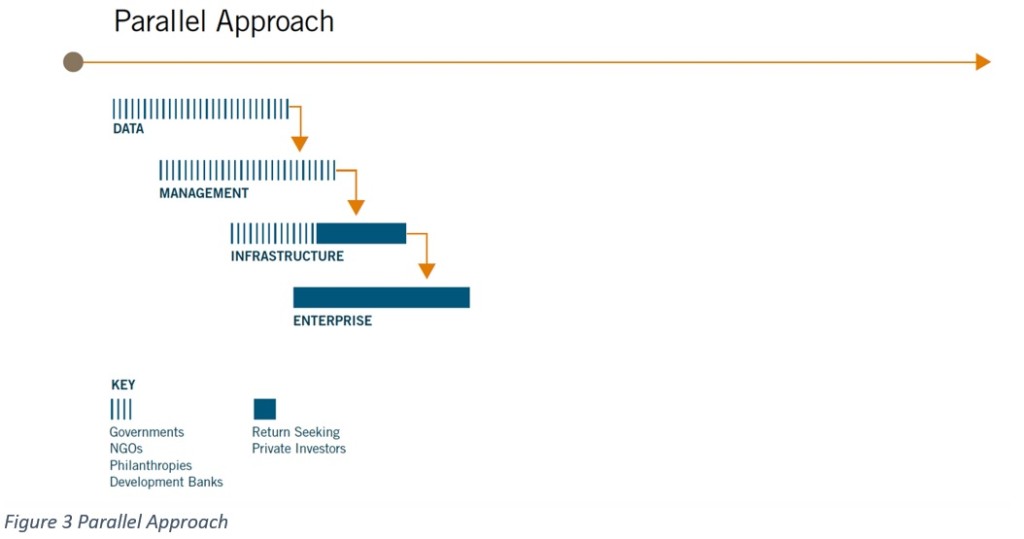

- Finally, test a new, “parallel” investment model for combining philanthropic, government, and private sector funding to address fishery management. If successful, other emerging market fisheries can tailor the model.

We are currently seeking additional partners to join us in this lead firm pilot project. Please get in touch with us if you would like more information and/or would like to get involved.

Based on our experience in coffee, cocoa, tea, cashew, macadamia and honey value chains, we have plenty of experience on the advantages and disadvantages of working with producer organizations (POs), usually cooperatives (1). They often fail, riven by poor management, member disagreement and poor financials. Indeed,

Based on our experience in coffee, cocoa, tea, cashew, macadamia and honey value chains, we have plenty of experience on the advantages and disadvantages of working with producer organizations (POs), usually cooperatives (1). They often fail, riven by poor management, member disagreement and poor financials. Indeed,