Three years ago, we set out to to explore a perceived anomaly in the impact investment market. While sectors such as carbon and agriculture were attracting a range of capital investment in sustainable fisheries appeared to be neglected. Given the geographic scope, industry scale and potential impact, we wanted to understand the reasons behind the lack of capital.

Our conclusion, following three years of field based research and due diligence in three countries, five fisheries, and over 220 interviews with financial, corporate, government, community and NGO representatives, identified the following key constraints:

- Data

- Management

- Market differentiation

- Infrastructure

- Finance

- Lack of investable entities

The first two, data and management, are the most pressing constraints to the effective deployment of capital at scale in developing country fisheries (DCFs), as discussed in our recently released report, “Connecting the Dots”. Each need to be addressed simultaneously if equitable participation of the harvester is important to investors.

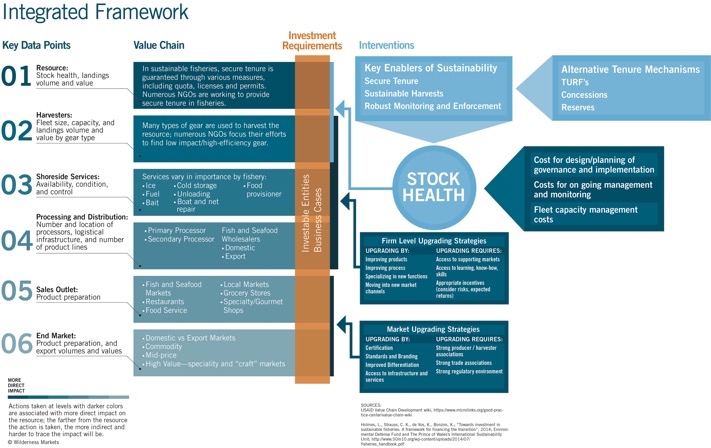

Concerning specific investments, there’s a fundamental need to distinguish between who and what benefits from value chain investments and investments in the drivers of stock health. While a healthy value chain benefits from a healthy stock, the benefits do not cut both ways, that is, a healthy value chain does not necessarily make stocks healthier; the drivers of stock health must be addressed.

Another general assumption holds that by changing the practices of one or two players in the value chain, we can secure stock health – this was found to be exceedingly unlikely in the open access system of fisheries which suffer from the tragedy of the commons. Addressing artisanal tuna harvester needs is socially and potentially economically positive, but it is difficult to prove environmental benefits if the next village over has unrestricted access – along with the purse seine factory fishing boat from the country next door!

The drivers of stock health are all external to the value chain, and, unfortunately, most financial interventions are reliant on the value chain in order to secure repayment. This disconnect is seldom recognized by practitioners, and it is often assumed that by changing the practices of one or two players in the value chain, we can secure stock health. At the other end of the spectrum are improvements aimed at stock health and improved socio-economics for fishing communities that rely on the “build it and they will come” theory, failing to integrate harvesters and buyers into improvements.

Our findings are that value chain based investments in open access systems are unlikely to improve environmental outcomes, and, in practices, are likely to accelerate resource extraction, in some cases, of already pressured stocks and resources.

Our research also identified significant investments in fisheries are an ongoing reality in many DCFs. Whether from the private sector (DDI and DFI data), and from national governments, fisheries are well capitalized.

The inequality experienced by artisanal harvesters is not, in our view, an issue of capital. It is a systemic failure, requiring multiple components be addressed simultaneously

There is an urgent need to focus efforts on improving the drivers of stock health in DCFs, over and above deploying yet more capital into the value chain without investment in stock health.