The Finance Gap in Sustainable Wild Capture Fisheries

Over the past few years, three broad strategies have evolved to address the challenge of achieving sustainable wild capture fisheries. These consist of:

- Addressing governance, regulation and policy

- Providing preferential access to markets via certification mechanisms and Fishery Improvement Plans

- Aggregating mission aligned capital

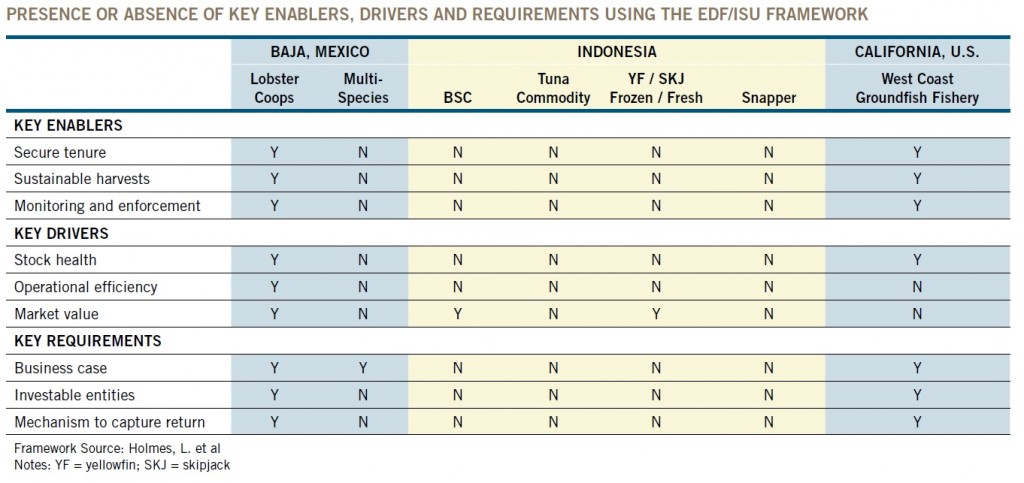

While each of these strategies have merits in and of themselves, they function best if their implementation is aligned, particularly in emerging markets where parallel or consolidated approaches are more likely to succeed than a serial approach. The implementation of these three strategies independently of each other often result in distortions that misalign incentives. As a consequence, this lack of alignment has resulted in few real world business examples or models that can effectively scale across fisheries, geographies and communities. Despite the attractiveness of economics of fisheries reform in at a macro level, the financial implications for practitioners in the real world have been challenging.

We especially note the development of mission aligned capital for sustainable fisheries in the past year. The Althelia Sustainable Oceans Fund and the Rare Meloy Fund are now either operational, or close to being operational. These new facilities represent important progress in this space.

While these represent important steps forward, they do not, as of yet, address the demands of current market conditions, particularly in emerging markets. Based on our field assessments in Asia, Latin America, parts of Africa and the United States, the reality is that the majority of the demand lies in defining, developing and testing sustainable fisheries instruments and models that may, one day, be eligible for the Meloy Fund or the Oceans Fund.

One sequence of fund development is to a) prove a concept, b) grow and refine and c) to deploy large scale capital (courtesy of Dalberg Global Advisors).

- Prove the concept – at this stage, practioners are testing financial instruments and models in a variety of settings with a wide variance of risk – returns and a great deal of tail risk. Transactions are often small, with high transaction costs, and with limited to no track record. While the Meloy Fund may most closely approximate these characteristics, the Funds requirements and relatively high return requirements and minimum transaction sizes remain a mismatch for the sector.

- Grow and Refine – at this stage, practioners are aggregating small scale proven models into larger vehicles; allocating and pricing risk appropriately; have a track record to demonstrate risk returns and an experienced team.

- Deploy Large Scale Capital – at this stage, practitioners are able to deploy large pools of institutional capital towards proven concepts; have more stable returns with lower tail risks and lower transaction costs as well as strong comparable track records for the sector and fund managers.

Based on our reviews, in the absence of financial instruments and model with documented and understandable risk, the sustainable wild capture fisheries sector appears to have a significant funding gap at the “Prove the Concept” stage. Resources are required to define these instruments and models, ideally with existing sector participants, many of whom are searching for approaches to transition NGO driven projects to investable entities with very limited success to date.

In reality, there is a significant pool of potential projects in the form of Fishery Improvement Plans, fishery projects, blue economy projects and alternative livelihood projects in many geographies. While Wilderness Markets has developed a systematic analysis of the potential investment opportunities in a number of fisheries, we have been struck by the rather random approach to this challenges and the lack of resources to systematically support the transition to investable entities that may, one day, be eligible for investment from the Meloy Fund or the Oceans Fund.