Industry stakeholders understand that overfishing undercuts long-term value and prevents realization of full economic potential in local communities. The question is, what to do about it? Wilderness Markets and Blue Star Foods collaborated on a pilot program to develop one potential solution.

Problem

Rising demand for seafood combined with limited public spending on fishery management systems has led to overfishing worldwide. As of 2013, almost a third (31.4 percent) of fish stocks were fished at biologically unsustainable levels, a 10 percent increase since 1974 (FAO 2016). In 2016, just over 58 percent of fisheries were considered fully exploited, with no expected room for further expansion (FAO 2016). Recent research indicates that these numbers are actually underestimated: FAO statistics do not include thousands of small-scale fisheries, recreational fishing, accidental catch of non-target species, and illegal fishing because they aren’t measured (Costello et al. 2012; Pauly and Zeller 2016). In addition, global trends mask the fact that many individual fisheries have collapsed and fishing boats have moved on to exploit new species (CEA 2012). This undercuts fisheries’ ability to provide long-term social and economic benefits to the local communities.

Wilderness Markets and others in numerous fisheries have conducted extensive value chain research. This research indicates that while the harvesters tend to bear the costs of fisheries management improvements, the economic benefit tends to be captured by participants further up the value chain – aggregators, processors and exporters. This is particularly the case in emerging market fisheries, where several factors collide:

- The inability to evaluate stock status and fishery conditions, due to the lack of reliable fishery data and track records, make it difficult to assess investment risk and rewards.

- The current open access nature of fishery and the absence of tenure rights and enforcement mechanisms do not allow the benefits of fishing improvements to accrue to specific fishermen.

- The large, numbers of individual, unregulated fishermen, who tend to operate opportunistically, making it costly to negotiate and monitor fishery improvement agreements.

- The lack of successfully tested models for implementing traceability measures means that there are few investment opportunities and few models to emulate.

Using Blue Swimming Crab in Indonesia as an example, research shows that while processors in the value chain stand to benefit from improved BSC management, these companies do not typically invest directly in helping fishermen transition to sustainable practices due to the above factors. While many processors are interested in supporting sustainability, it is difficult for them to demonstrate reliable return on investment (ROI) to their investors to justify financing these efforts.

Because of these hurdles, fishery improvement efforts end up relying on ongoing philanthropic support or government subsidies, without reliable economic incentives for change built into existing business models.

Sumatran Fisherman with Blue Swimming Crabs

Wilderness Markets teamed with Blue Star Foods, a Miami, Fla.-based distributor of quality crabmeat, to explore creating an industry-led sustainability initiative within the BSC fishery in Indonesia, Indonesia with the hope it would provide a blueprint for other fisheries.

Approach

The first step in our approach was to gain a clear understanding of the concerns and needs of impact investors, believing this understanding will allow development organizations, NGOs, and others, to better sequence their interventions (that is, through their risk instruments, matching capital, public and concessional financing, technical assistance, and macro-level reforms, and policy initiatives) to encourage private sector participation while leveraging and preserving scarce public dollars for critical public investments.

We specifically explored the central challenges that keep impact investors from participating in sustainable fisheries:

- A lack of reliable fishery data

- Ineffective fisheries management

- Unreliable infrastructure systems

- A paucity of investment-ready enterprises

The team analyzed the current state of fishery data collection, resource management, infrastructure systems, and enterprise capacity in the fishery. We found that — like many fisheries in emerging markets — the BSC fishery lacked reliable data and, despite new national fishery policies, functioned largely without effective management and enforcement. We also found strong, established commercial and social relationships within the value chain that point to the power and influence of a small group of 16 processors that buy BSC from 400 mini-plants that, in turn, purchase crab from more than 65,000 fishermen.

Using the data collected, we identified and analyzed three models for sequencing and combining different sources of capital to overcome obstacles:

- Serial approach: Public and philanthropic funders first support the establishment of strong governance arrangements, improved data collection, and fishery management. Once these initiatives mitigate some of the risk associated with a fishery investment, then return-seeking investors are incentivized to finance sustainable infrastructure projects (often through public-private partnerships) and/or enterprises along the value chain, focused on outcomes that achieve a triple bottom line: social responsibility, economic value, and environmental impact.

- Consolidated approach: Governments negotiate agreements with a single private sector entity or cooperative to delegate fishery management responsibilities. The private firm or cooperative then simultaneously invests in fishery data, management, infrastructure, and triple bottom line enterprises.

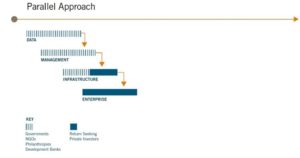

- Parallel approach: A range of investors and other stakeholders (for example, governments, nonprofit organizations, fishing collectives) develop coordinated investments to improve fisheries data, management, infrastructure, and triple bottom line enterprises. Efforts can be separately funded, but they work in tandem and share the ultimate goal of achieving sustainable catch with an appropriately capitalized and profitable fishing sector.

Outcome

Based on our findings, we identified the “parallel approach” as the most appropriate for the BSC fishery in Indonesia. We coupled this with a “lead firm strategy,” in which a “market maker” firm ensures market access and aligns economic incentives for change. This industry-led sustainability initiative draws on the experience Wilderness Market has in a number of other sustainable agricultural markets.

In this case, the strategy works with a U.S. based lead firm, to create financial and social incentives to

Lead firm and harvester meeting

enable fishermen to transition faster to sustainable fishing practices and improve management. Through its purchasing power and economic and cultural relationships, the lead firm is in a strong position to influence the practices of a range of processors, who have commercial and cultural relationships with a network of mini-plants, collectors, and fishermen.

Together with the lead firm and local harvesters, we developed a pilot model based on a partnership between the lead firm and a producer organization or fishing cooperative. The model brings together limited amounts of philanthropic capital and relies primarily on private capital to provides financial, social, and environmental returns. This return-driven model includes:

- Purchase commitments based on price, quality and standards

- Investments in fishermen cooperatives to motivate gear improvements and sustainable practices

- Improved fishery data collection and traceability

- Support for harvest control compliance

The pilot project is designed to align and attract private, return-seeking impact investment to the fishery and complement ongoing work by NGOs in the region to improve fishery management. Critically, it is designed to address the lack of loyalty in relationships between local harvesters and the supply chain, thus providing a basis to address the return on investment for improved fishery management.

Provision of ice is a key concern

We expect this approach will enable local fishermen to better organize, adopt sustainable practices faster than waiting for the government to create and enforce management changes on its own, and address the economic hardships fishermen face when resolving changes in fishery regulations. It will also help bolster local business and community support and advocacy for more effective fisheries management policies and enforcement through a legal, local cooperative structure.

The new facility focuses on utilizing good data to address a prioritized sequence of fishery management measures related to size, sex and seasonality in BSC fisheries in Indonesia[1], where illegal and destructive fishing practices are pushing crab populations toward collapse. By strategically investing capital in priority data, fisheries management[2] and harvest related changes, the facility proposes to share the upside of recovery with local harvesters and business through the value chain.

Vessel tracking unit to improve traceability

This impact initiative is aligned with local regulations in Indonesia[3] to further assure social, environmental and economic impact.

As a result of better data collection, alignment of economic incentives and effective supply chain management, the fishery will produce higher yields of BSC. It will also provide a traceable, sustainably harvested product that will have a competitive advantage in key U.S. and E.U. markets where the lead firm and supporting investors will be able to recoup their investments in sustainable practices.

Ultimately, we hope to help establish a management or governance unit of key stakeholders — including fishers, mini-plant operators, district and provincial heads, processors, scientists and APRI representatives (the association of Indonesian crab processors) — in order to address factors in the enabling environment, which will strengthen this pilot.

Why It’s Successful

We believe this pilot will help overcome a key roadblock in creating sustainable fisheries in emerging markets: it provides a concrete, “proof of concept” that can demonstrate the financial success of sustainability investments and encourage other fishing industries to design similar programs.

By embedding sustainability requirements within existing value chain relationships and practices, we will:

- Demonstrate the financial viability of investments in fishery data collection and management, thus attracting additional private sector action and corporate investment in, and support for, these practices.

- Create new norms in the fishery that are sustained because of their business value rather than relying on ongoing philanthropic support; government subsidies or inefficient enforcement to succeed.

- Provide clear and reliable financial benefits for small-scale harvesters to make gear changes, follow harvest control measures, and take on other sustainable fishing practices. This alignment of immediate economic well being with sustainability practices will improve compliance and reduce the short-term, negative impacts of fishery restrictions on local economies and communities.

- Test a new, “parallel” investment model for combining philanthropic, government, and private sector funding to address fishery management issues. If successful, this model can be tailored and applied to other fisheries in emerging markets.

While we are starting with BSC fisheries Indonesia, the problems these fisheries face are common in a number of emerging market fisheries. We are building a model that can be rapidly modified, applied and scaled in a variety of fisheries around the globe.

We believe the pilot BSC program will help overcome a key roadblock in creating sustainable fisheries in emerging markets because it provides a concrete “proof of concept.”

——

[1] “Indonesian Blue Swimming Crab Value Chain Summary”. 2015. Wilderness Markets. http://www.wildernessmarkets.com/portfolio/indonesian-blue-swimming-crab-value-chain-summary/

[2] Jeremy Prince. 2015. Indonesia BSC Spawning Ratios. Unpublished data from personal communication.

[3] RPP Rajungan, decree number 56/Permen – KP/2016 for BSC Fisheries Management

Figure 1 Fishing vessels, California, USA

Figure 1 Fishing vessels, California, USA Figure 2 Women harvesting seaweed, Zanzibar, Tanzania

Figure 2 Women harvesting seaweed, Zanzibar, Tanzania Figure 3 Women sorting catch, East Java, Indonesia

Figure 3 Women sorting catch, East Java, Indonesia Figure 4 Honolulu and Waikiki Beach economy includes tourism, fishing and shipping, Hawaii, USA

Figure 4 Honolulu and Waikiki Beach economy includes tourism, fishing and shipping, Hawaii, USA