![Iceland - Siglufirði Siglufjörður By Hansueli Krapf This file was uploaded with Commonist. [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/4/4b/2014-04-29_11-04-49_Iceland_-_Siglufir%C3%B0i_Siglufj%C3%B6r%C3%B0ur.JPG)

Iceland – Siglufirði Siglufjörður By Hansueli Krapf This file was uploaded with Commonist. [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

Icelandic cod first came to our attention at Wilderness Markets when we were collaborating with Future of Fish on research into financing needs in the US Northeast Multispecies Sector Program. How can cod from, Iceland, over 2000 miles away be not only cheaper but of equal or better quality than cod caught from just outside your proverbial front door?

A series of papers highlights important developments and key factors in the success of the Icelandic cod value chain since the ‘90s. The series include:

- The Effects of Fisheries Management on the Icelandic Demersal Fish Value Chain, 2016[1]

- A Comparison of the Icelandic Cod Value Chain and the Yellow Fin Tuna Value Chain of Sri Lanka, 2010[2]

- The Role of Fish Markets in the Icelandic Value Chain of Cod, 2010[3]

- The Importance of SMEs in the Icelandic Fisheries Global Value Chain, July 2009[4]

- Structural Changes in the Icelandic Fisheries Sector – A Value Chain Analysis, 2008[5]

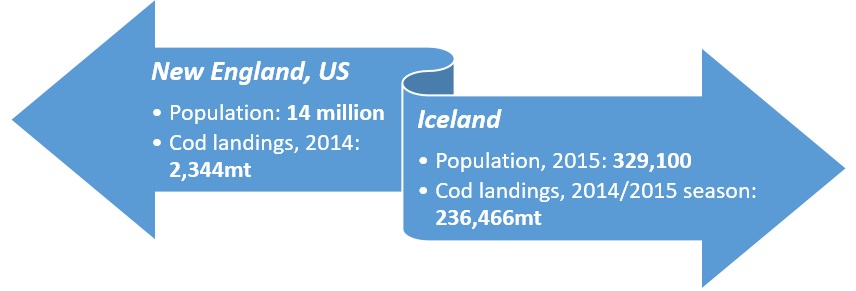

Before digging in too far, two aspects of the Icelandic versus the New England value chains can’t be overlooked—the relatively small population of Iceland and the relatively high landings of cod. For disputed reasons (climate change, better management, etc.) Iceland has a much healthier, i.e. more abundant stock, and hundred-fold greater landings than New England. Along with much higher landings, a far lower population means a robust export market.

[6]

Key factors and developments:

- Increased efficiency at multiple levels of the value chain has helped improve value

- Domestic value creation, specifically in the form of fresh fillets, has added significant value

- Information flow (availability of information) and knowledge drive value

- Use of marketing information to govern the value chain through vertical integrated companies and fish auction markets

- Fish markets (auctions) improve efficiency and improve the consistency of supply for the value chain by acting as clearinghouses and support speculation

- Consolidation of vessels, fishermen, processors, processing workers, and quota ownership have occurred in significant number

- Increased specializations in fishing and processing

An interesting aspect that warranted a whole paper is the role of the fish markets, effectively online auctions, wherein all bidding is done through one computerized system owned by 15 independent markets since 2000. These private markets only handle 20% of the landings by volume but have a high value in terms of value chain efficiency because they allow for specialization (buyers can sell or swap species not needed for production), provide stability (buyers can ‘top-up’ if they are short on supply) and creates market-driven value for species. The rise in general groundfish prices by 20% from 1999 to 2008 is thought to be partially attributed to the fish market system.

Some key aspects of the Icelandic cod value chain, like low human population in Iceland and abundance of target species in their waters, don’t readily translate to Wilderness Markets’ recent focus on the Indonesian and U.S. West Coast fisheries. Others do. For instance, in the paper on the importance of small and medium enterprises (SMEs), the increase in vertically integrated companies means those companies have better control of the reliability, quality and delivery of fisheries products. Their competitive advantages are related to quality assurance knowledge, good logistics and dedicated export and sales management. On an almost reverse timeline for the U.S. West Coast groundfish fishery in California, fish handling in Iceland improved in the ‘90s and ‘00s by investments in better onboard cooling systems, shorter fishing trips and logistics improvements.

In the 2016 paper, they also describe the structure of the value chain before the export licensing system was abolished in the 1980s—importantly, and with implications for other value chains – the three large marketing and sales organizations that controlled most of the fish failed to send market signals back to producers. The new, vertically integrated companies that replaced these organizations heeded signals from foreign customers and improved product quality and successfully added value domestically by switching processing to Iceland instead of overseas.

We have witnessed this same disconnect in many other fisheries; fishermen don’t seem to have any idea about the needs and demands of the end markets and have no incentive to meet these demands. In one of the most telling statements in the series, an interviewee states, “They [the Norwegians] are still mostly thinking about catching while we have reached the point where we think about serving the market.” Most fishermen have not yet been able to reach this stage, hindering their ability to realize improved value for their work.

We’re hopeful that the end-market research currently underway in California will provide market data that can be turned into increased value for the harvesters working diligently to promote sustainability.

[1] Knútsson, Ö., Kristófersson, D. M., & Gestsson, H. (2016). The effects of fisheries management on the Icelandic demersal fish value chain. Marine Policy, 63, 172-179..

[2] Knútsson, Ö., Gestsson, H., Klemensson, O., Thordarson, G., & Amaralal, L. (2010). A Comparison of the Icelandic Cod Value Chain and the Yellow Fin Tuna Value Chain in Sri Lanka.

[3] Knútsson, Ö., Klemensson, Ó., & Gestsson, H. (2010). The Role of Fish-Markets in the Icelandic Value Chain of Cod.

[4] Knútsson, Ö., Gestsson, H., & Klemensson, Ó. (2009, July). The importance of SMEs in the Icelandic fisheries global value chain. In IXX EAFE Conference Proceedings (pp. 6-9).

[5] Knútsson, Ö., Klemensson, Ó., & Gestsson, H. (2008). Structural changes in the Icelandic fisheries sector-a value chain analysis.

[6] New England Population: http://www.dlt.ri.gov/lmi/census/pop/neweng.htm

Iceland Population: http://www.iceland.is/the-big-picture/quick-facts

US landings: http://www.st.nmfs.noaa.gov/commercial-fisheries/commercial-landings/annual-landings/index

Icelandic landings: http://icefishnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/Marko-partners-%C3%ADslenski-kv%C3%B3tinn.png