West Coast Pilot – Culinary Workshop

A previous post outlined our pilot project in California with Changing Tastes; this post provides a peek into a culinary workshop that is part of the planning phase.

Purpose

As part of our work to reintroduce local fish back into local markets in California, our foremost consideration is how to reintroduce them to our plates and palates. Without delicious dishes and high quality products, winning back a space on the plate will be impossible.

To discover how local fish can create a winning combination of flavor, presentation, and affordability for chefs in corporate dining, our partner Changing Tastes arranged a culinary workshop in California. More than a dozen chefs and several sustainability managers from the same or similar groups joined us in mid-November at a test kitchen in the Bay Area to develop the recipes and messaging needed to successfully bring back Californian West Coast Groundfish.

Palate and Pocket

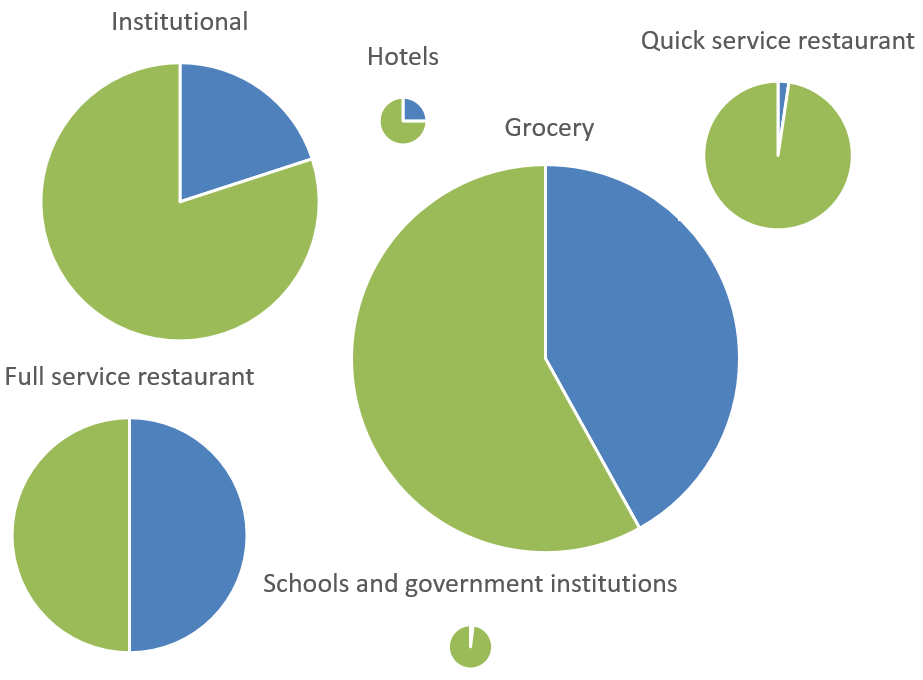

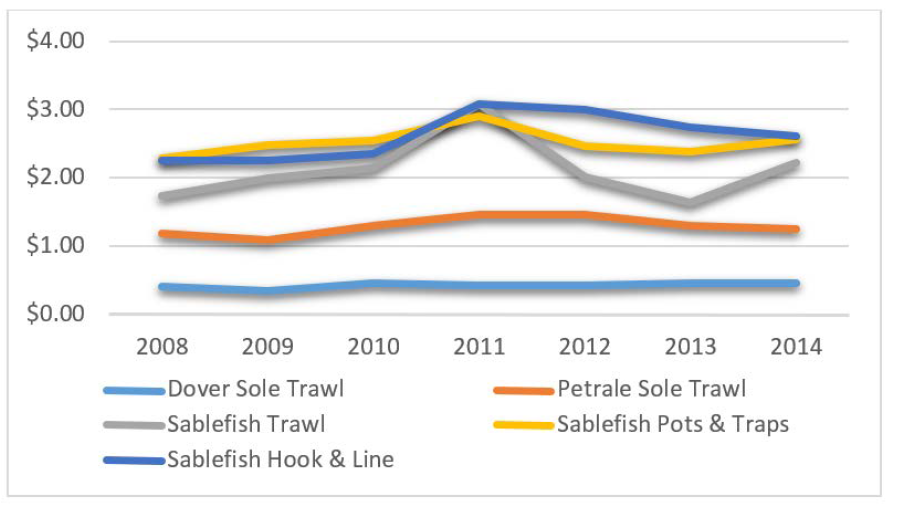

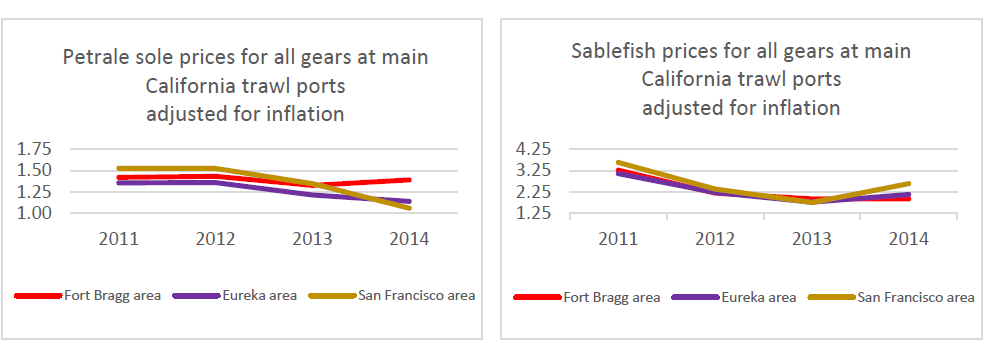

To explore which fish could please both palates and pocketbooks, the chefs spent the morning preparing a sampling of locally-caught fish, including Dover and petrale sole, boccaccio, chilipepper and black gill rockfish, and sablefish (AKA black cod) provided by Real Good Fish. These fish represent the spectrum of species that are part of the West Coast Groundfish program, one of the most sustainably managed fisheries in the world, and one that has the fish to prove the stocks are healthy. These are fairly common landings that span from very inexpensive Dover to higher-end sablefish. The variety of textures, thicknesses and tastes were highlighted in Latin and Asian-inspired themes, such as black gill fish tacos with mango slaw (Chef Ochoa), petrale-coconut ceviche (Chef Fogata), black and white coconut crusted black cod (Chef Thomas), and steamed Szechuan boccaccio (Chef Hernaez).

Heart and Mind

Equally important to taste and cost is persuading diners to try these new dishes. In a nearby space, restaurant industry marketing and communications executives as well as sustainability managers and representatives of groups that support sustainable seafood brainstormed marketing ideas for the dining spaces where the fish will be offered to diners next spring.

Common themes included emphasizing that the fish is locally-caught in California. They noted that “local” often implies fresh to diners. Including a map of the different ports where the fish originates from for the pilot, and identifying fishermen and women from each was another popular theme.

Marketing experts, chefs, sustainability managers and others agree on not using the word “groundfish” in marketing materials. This group and others realize that this collective term for these species isn’t one that necessarily appeals to diners, nor does it help them understand the diversity of species and flavors within the broad category.

Pilot Evaluation

Among potential evaluation methods and data points, our participants identified these as the most likely:

- On-site, established food focus groups

- Measurement of orders by volume

- Gauging the relationship between price of dishes and purchases

- Comparison to sales of other seafood dishes

- Comment cards

- Online commenting system

- Surveys, potentially with incentives, and/or provided in a quick format via touchpad at the point of purchase

- Querying the culinary team during and after the pilot

Post-workshop steps

Our next tasks are confirming which specific dining halls and cafes will participate from each of the corporate dining partners and confirming likely order volume by species or species group, e.g., petrale sole is a species and rockfish is a species group. Almost simultaneously, we will work with the corporate dining partner and their existing distributors to determine the likely sources, feasible start dates, and volumes. We look forward to sharing updates as this work progresses in 2018.