Characteristics of Successful Sustainable Fishery Initiatives

Over the past six years, Wilderness Markets has assessed sustainable fisheries investment opportunities in more than fifteen different wild capture fisheries worldwide. Our specific objective is defining how to make conservation-based approaches a viable financial alternative to current wild capture fishing practices.

We have enjoyed working with numerous international and national partners on field assessments, desk reviews and systemic fishery improvement project (FIP) assessments. Much of our public work and partners can be reviewed at this link. Fisheries assessed ranged from the United States, Mexico, Indonesia, the Dominican Republic, Grenada, Guyana, Chile, and four Caribbean-wide fisheries. Along the way, we have also reviewed a number of fisheries in Africa.

Behind these public reports are a series of financial models we created to quantify the viability of alternatives considered in different fisheries. These models move beyond the scientific and policy recommendations associated with fishery reform to account for the financial implications associated with existing or proposed measures. These models weigh the financial costs and benefits of changes in management, data collection and use, infrastructure and capacity development in the context of existing value chains and markets.

Whereas others have ably demonstrated the potential upside associated with fisheries reform through significant economic modeling,[1]and others have documented key characteristics of FIPs,[2] we have focused on how and where the specific financial benefits may be realized in a value chain. We identify how the “upside” may be used to compensate for the costs of fisheries reform and improvement such as gear change, improved management, etc. Our focus has been on the financial implications for fishery participants, especially fishers.

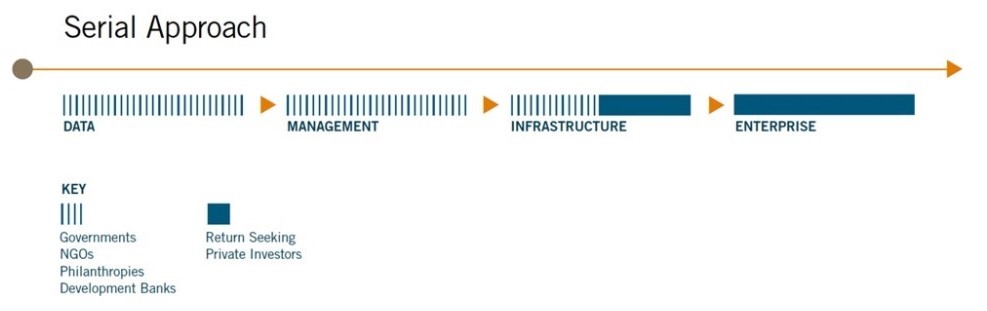

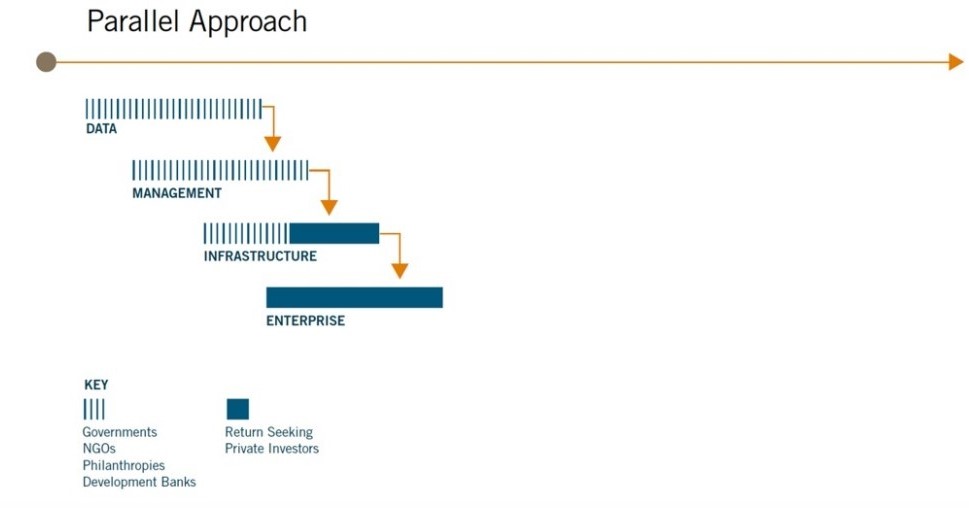

Through our work and others’, the variables listed below have been identified as having a direct impact the financial viability of fisheries reform. These five variables have been examined across a range of fisheries and found to be consistent. It is important to note that these operate in the context of sustainable fishing interventions, most likely in a “parallel” model.

- Product value

- Stock recovery cycle[3]

- Infrastructure Access[4],[5]

- Supply chain length[6], [7]

- Organizational homogeneity and capacity[8]

These variables are focused specifically on the potential likelihood of securing the financial incentives necessary to address the costs of fisheries reform or improvements, i.e., ability to pay for conservation measures through the improved value of the fishery. These benefits may then be utilized to justify reform or directly support sustainable fishing practices.

The priority quantitative variables that have a direct impact on the financial equation are:

Product Value

Value refers to not only the price of the seafood, but also to the margin retained by the participant in the value chain, whether fisher, first receiver or processor. This is a combination of the price, operational capacity, input costs and volumes associated with a participant.

Products handled by participants capable of securing comparatively high value in seafood markets were found to be more capable of absorbing the incremental costs associated with fisheries reform and conservation focused measures. Lower value products – either due to the inherent value of the stock, low volumes, operational inefficiency or poor capacity leading to low margins are less likely to be viable. The willingness of participants to engage in changes in practices such as gear change and harvest control regulations, is directly proportional to the value generated by the seafood product and realized by the participant.

Stock Recovery Cycle

Life cycles, fecundity, biomass levels, fishing effort mortality, predation and habitat health are all critical components in defining the costs of conservation related measures. Short recovery cycles reduce the wait time to realize benefits in a fishery, capping social, political and financial costs associated with fisheries reform.

The primary qualitative factors that influence the financial equation are:

Infrastructure Access

Domestic and global supply chains require sanitary and safe foods, therefore access to appropriate storage and transport is a significant driver of product quality and value. In seafood, this typically means access to HACCP compliant facilities able to reliably provide clean ice, cold storage and timely transportation. The absence of these factors negatively impacts value.

This variable is routinely exploited by supply chain participants (including well meaning development organizations) to attempt to integrate new products into global and domestic supply chains. Unfortunately, negative social and environmental consequences are not always considered by these participants, nor is there typically a simple mechanism for integrating or compensating fishers or others for improvement costs.

Supply Chain Length

Supply chain length includes both the geographic distance and the number of participants “touching” a product in the supply chain. Extensive travel distances between points of harvest and market drive up costs of transportation, ice and storage, and lead to product deterioration. Each “middleman” in the supply chain adds handling and cost margins to the product. While these costs may be absorbed by the end market, long supply chains decrease the likelihood of compensating those bearing the cost of fishery reform and improvement, usually fishers.

Organizational Homogeneity and Capacity

When considering artisanal and small scale fisheries, community cultural homogeneity has been identified as a critical component of community based fisheries management and reform efforts. Successful efforts are entirely dependent on alignment around goals[9], which is easier to achieve in geographically remote, culturally homogenous communities. Regardless of the financial upside, heterogenous community efforts close to major cities are challenging.

At the corporate level, strong leadership and the ability to effectively respond to market signals has been well documented in value chain literature and in pilot projects we have tested.

At its base level, the presence of a functioning investable entity is a significant advantage in successfully addressing the characteristics identified above.

Based on our review of a range of different fisheries, the above characteristics have a significant impact on the success or failure of sustainable fisheries initiatives, particularly in emerging market contexts where the financial and social implications of fisheries reform are often ignored by the conservation community.

Unless these factors are integrated into projects aimed to curb overfishing, conservation efforts are unlikely to succeed and the unsustainable status quo is likely to continue.

We welcome your comments, thoughts and views on the above.

[1]Costello C, Ovando D, Clavelle, T, Strauss, K, Hilborn, R, Melnychuk, M, Branch, T, Gaines, S, Szuwalski, C, Cabral, R, Rader, D, and Leland, A. (2016). Global fishery prospects under contrasting management regimes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.113. 201520420. 10.1073/pnas.1520420113.

[2]https://www.ceaconsulting.com/wp-content/uploads/Global-Landscape-Review-of-FIPs-Summary.pdf

[3]http://investinvibrantoceans.org/wp-content/uploads/documents/Executive_Summary_FINAL_rev_1-15-16.pdf

[4]Anderson J, Anderson C, Chu J, Meredith J, Asche F, Sylvia G, et al. (2015) The Fishery Performance Indicators: A Management Tool for Triple Bottom Line Outcomes. PLoS ONE10(5): e0122809. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0122809

[5]Basurto X, Bennett A, Hudson Weaver A, Rodriguez-Van Dyck S, and Aceves-Bueno J-S. 2013.

Cooperative and noncooperative strategies for small-scale fisheries’ self-governance in the globalization

era: implications for conservation. Ecology and Society. 18. 10.5751/ES-05673-180438.

[6]Ibid.

[7]Wilderness Markets. 2016. Connecting the Dots: Linking Sustainable Wild Capture Fisheries Initiatives and Impact Investors.http://www.wildernessmarkets.com/our-work/connecting-the-dots/

[8]McCay BJ, Micheli F, Ponce-Díaz G, Murray G, Shester G, Ramirez-Sanchez S, and Weisman, W. (2014). Cooperatives, concessions, and co-management on the Pacific coast of Mexico. Marine Policy,44,49–59. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2013.08.001.

[9]Csaky, Eva (2014) Smallholder Global Value Chain Participation: The Role of Aggregation (PhD Dissertation, Duke University)